Professor Helen Milroy: Strengthening support services for children’s mental health

WA 2021 Australian of the Year, Professor Helen Milroy, talks about the unravelling of her career, merging traditional and modern paths of medicine and her creative alter-ego.

Every article written about Professor Helen Milroy to date lauds her as Australia’s first Indigenous doctor. It’s a badge of pride she wears with deep reverence and humility. But she also doesn’t miss an opportunity to acknowledge her family and community’s generation of traditional doctors.

“I’m the first Indigenous doctor educated in Western medicine but there have been many Indigenous doctors before me,” she says. “And considering how healthy Indigenous people were at the time of colonisation, I think our healers did a pretty good job!”

Helen is a descendant of the Palyku people of the Pilbara region of Western Australia. She was raised by her mother and grandmother in Perth during a time she remembers as “difficult for Aboriginal families because of the fear of children being taken away.”

“Fortunately, I stayed with my whole family during that time. I had a wonderful childhood because my grandmother was always around for me turn to in times of uncertainty. We spent a lot of time together. She was my safety net.”

Helen’s grandmother, Daisy, also had her healing ways and taught her young granddaughter how to care for others from a cultural perspective- treating them like family.

Unsurprisingly, Daisy’s generosity and kindness strongly influenced Helen’s own compassion and planted the seeds of her future career in medicine and mental health.

Merging two paths of knowledge in healing

After graduating from the University of Western Australia, Helen spent the next few years as a general practitioner and consultant in childhood sexual abuse at Princess Margaret Hospital for Children. Both experiences opened her eyes to the lack of understanding of trauma in children and especially of the generational trauma felt by Indigenous children.

In the 25 years that have passed since then, she has pioneered research, education and training in Aboriginal and child mental health, and recovery from grief and trauma.

She has also played key roles on numerous mental health advisory committees and boards, including the National Mental Health Commission. In 2018, the AFL made history by appointing her as its first Indigenous Commissioner. This also made her the third woman on its governing body.

Yet she bats away any praise of her ambition.

“I was a fairly determined kid who just kept going,” she laughs. “I didn't have a plan. I didn't set out to do certain things - they happened along the way. Each time an issue came up that interested me, the path would unravel a little more.

“As a young doctor, I saw things I thought should change or be improved. When you've grown up in an Aboriginal family and see the huge burden the community carries, it compels you to try harder to make a difference.”

While pulling shifts in the Child Protection Unit in the Children’s Hospital, Helen quickly realised that there weren’t any models of recovery for Indigenous communities at the time. That’s when her career path unfurled a little more.

“I decided to make Child and Adolescent Psychiatry my field of specialty,” she says. “I've always had an interest in kids and people's stories, and I wanted to work with trauma and cultural models to see if I could make a difference in this area.

“I started learning about the meaning of health and healing from an Indigenous perspective, and the meaning of illness and symptoms from a psychiatric perspective. Then I developed training courses, a curriculum and models of understanding that combined Indigenous knowledge with Western science to get us the best outcomes.”

One of Helen’s most profound experiences was during her five years as commissioner for the Australian government's Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse from 2013. She describes it as “intense, inspiring and disturbing.”

While she expresses hope that the Commission’s work has made Australia a safer place for children, she also voices frustration at the severe underinvestment in long-term services to support children’s mental health, especially in rural and regional communities.

In October 2020, Helen was named WA 2021 Australian of the Year for her trailblazing work in this space. Helen says she was both shocked and humbled by the privilege of having her career recognised in this way.

Using creative outlets to encourage imagination and for self-care

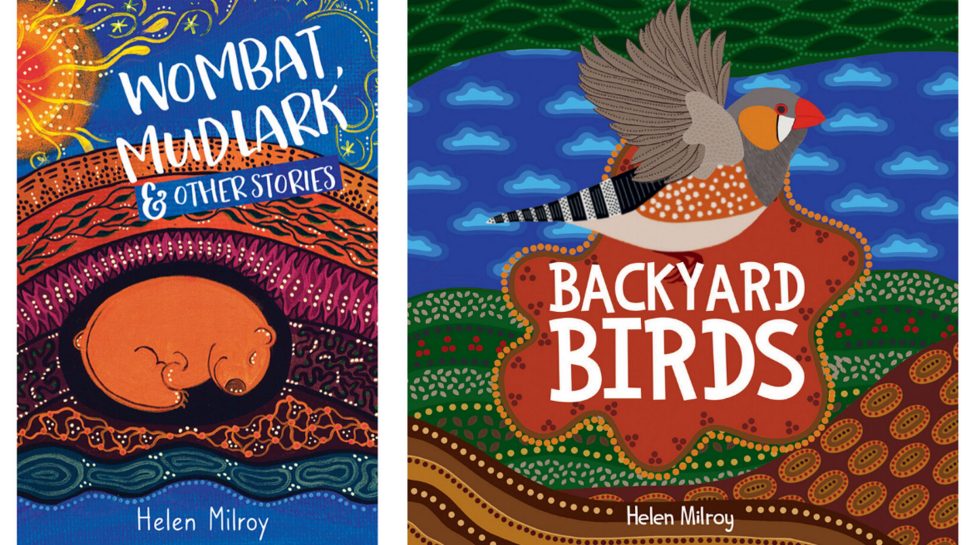

When she’s not wearing her psychiatrist hat, Helen is also an author and illustrator. As a doctor, she painted psychiatry concepts and wrote narratives that wound up being used in various reports and books. She also uses her painting in teaching to stimulate both sides of the brain and create a deeper learning experience.

More recently, she began writing and illustrating children’s stories. What started out as a means of encouraging children’s capacity for imagination, problem-solving and resilience took on a life of its own and has since resulted in four children’s books and a series.

“Storytelling and creating visual forms are a big part of Indigenous culture, she says. “They’re the oldest form of learning. And I love the idea of Indigenous storytelling because in that world everything is in relationship and is in balance. I think that's a wonderful ecological system for children to be embedded within.

“Being human is about being connected to everything - each other, our ancestry, our future and the natural world. That's part of Indigenous culture too. That sense of interconnection is what establishes our wellbeing and stops us feeling isolated and alone in this world.”